Thaddeus Rex Running in the Sun Again

Matthew Joseph Thaddeus Stepanek bled from his fingertips when he wrote. And he was writing a lot at the end of his life, when he was one of the most famous boys in the world. He left red traces on the computer he used to type his poetry, and on notebook paper when he wrote in pencil, and on his electronic piano, which he was learning to play, sitting in his wheelchair practicing Bach'sMinuet in G. He was barely a teenager. When he described the rare disease that caused the bleeding, he wrote with a keening grace—there was a storm inside him, and he knew it would never allow him to grow up. "I am both living and dying at the same time," he said, explaining to his mother that his body was failing but his mind and spirit were alive. His mother called him Mattie.

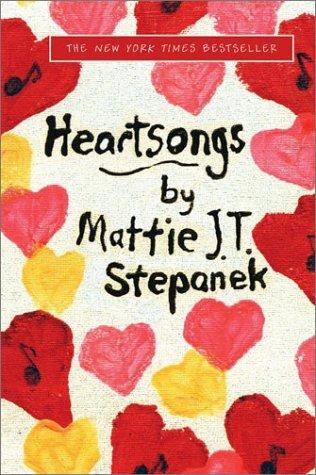

There was a storm inside Mattie's mother, too. The same rare disorder, dysautonomic mitochondrial myopathy, a condition similar to muscular dystrophy. Jeni Stepanek, watching her son from audiences and green rooms, from the kitchen table of their one-room apartment as he wrote, as her son's books of poetry—Heartsongs and the six that followed—became improbable national bestsellers. As he became a regular onOprah andLarry King and established an unlikely friendship with Jimmy Carter, who called him "the most extraordinary person who I have ever known." Jeni's life, in many ways, being Mattie's.

He was so famous that it was Jeni who kept stalkers out of his room at Children's hospital in DC—the boy poet with a gap between his front teeth and a tracheostomy tube in his throat that looked like a plastic necktie. Jeni who let him use the alias Sean Astin, the actor who played Samwise in his favorite series of movies,Lord of the Rings. Jeni who loved another alias he wanted to use, Paprika, a word he almost sang, to nurses, "PAPRIKA! PAH-PREE-KA!"

Jeni who played Scrabble with him in the hospital, the board stained red from where his fingers had placed the tiles. Jeni who let him keep a remote-controlled fart machine, which he activated every morning during the doctors' rounds. A mother who slept on the waiting room couch and on the tile floor, keeping the curtain around his bed open so he never felt alone and the light on near the bed because he was afraid of the dark.

It was Jeni who used a softer word for everything Mattie was afraid of, describing the spectre of his medical crises, his thoughts of death, as "hesitations."

Jeni, also bound to a wheelchair, who drove him in a full-size Econoline on speaking tours across America, Jeni who came up with a game to see which of them could name the most cereals, who in mountains and deserts sat in the seat while her son was asleep, in awe of what had become of their lives. It was Jeni, aghast, at McDonald's, where strangers pushed napkins for him to sign under his restroom stall, asking him toplease tell them something profound—one person asking him to bless the baby in her stomach. Jeni was there when Oprah kissed Mattie on the forehead, anointing him. The same show on which Mattie first described "heartsong," the word that endeared him to the world. "It's a message in my heart," he said. "A heartsong doesn't have to be a song. It can be your message, your feeling—some people might even call it a conscience. Even though that's not really what it is. It's what you feel you need to do."

A made-up word, one of many in his poetry, which Jeni encouraged. "I don't know the real word, but this is the word I'm using," he said.

"It's better than a real word," she replied.

He died a month shy of 14. It was Jeni who was next of kin at the funeral best remembered for Jimmy Carter's eulogy, who would look in on the Rockville park named after Mattie in 2008, who would remember the hilarious but also heartbreaking things Mattie used to say to her: "Weird Al is an absolute genius" and "My muscles feel like sour milk, and my heart feels like burning ice cream." One of the last was "Do not lie down in the ashes of my life," as though it were a line of his prose. Then he used another made-up word: "Take my message forthward."

For the past 13 years, that's what Jeni has done—honored his made-up word. Through her gradually failing heart and weakening muscles, through cancer and weekly rounds of chemo, through fibrosis of her intestine and a dozen other dysautonomic symptoms that are no longer just a storm in the distance, she has continued talking about him, his words still motivating her on the days when she doesn't want to get out of bed. Jeni doesn't have much time left; she is dying herself. But her son's poetry, his proclamations, everything he left behind—she's still spreading his message, while she still can, trying to figure out how to make it last forever.

Stories about him were ultimately the story of her—the story of a mother's love. He occupied 5,089 days in the middle of her life, the only one of her children who lived long enough for her to really get to know. The story of his ascension into the zeitgeist, and of his legacy, of his sense of humor, his kindnesses, his frustrations, his "hesitations"—now, at 58, those are stories she uses to explain the woman she has turned out to be, frail of body but strong in every other way. Starting with the story of how he was born.

The first thing she remembers is a sensation, and not merely the kicking and rustling in her stomach that only a mother could describe, but a different one that came to haunt her—a sensation of immutable dread. She was terrified that he would suffer, and then he would be gone. "When I found out I was pregnant with him, I cried and cried and cried," she says. "Not because I didn't want him but because I was aware of the suffering the child would go through. Most doctors suggested that I terminate the pregnancy, and many of my friends and most of my family thought I was an absolute monster to even get pregnant again. [I could only explain that] I would help this child develop some sense of purpose, no matter how short or how much suffering the life would have."

Jeni's first child, Katie, was born in 1985. She had dark hair and blue eyes and couldn't regulate her autonomic systems—her heart rate, breathing, digestion, blood pressure. She died suddenly at 20 months old. Jeni was told Katie was a fluke of nature, one in a billion odds of ever happening again. The same thing happened with Stevie, though. A little gob of skin with bright-blue eyes and red hair, born four weeks early with the same symptoms. He died when he was six months old.

"At this point, I was totally devastated," Jeni says. "I lost two babies in eight months—doctors had no clue why. They did say this had to be genetic: two kids, same symptoms. The odds of having a third child with this were almost impossible."

Early in 1989, Jamie was born, and it was clear that he had the same condition—the unnamed thing. Rather than wait for him to get sick, the doctors put him on life support, and for a long time that worked. Though he was tethered to oxygen, by the time he was 15 months old, he was actually singing the ABCs and counting his 123s. He lived like that for almost two years, and then he went into cardiac arrest after being in septic shock and was in a persistent vegetative state until he died at almost four years old.

Mattie was the most fragile—no one thought he would survive his first night. He needed CPR more than once, and most doctors were encouraging Jeni to institutionalize him. She was advised not to bond with him and was told to let whatever was killing him run its course. Doctors told her she was making him suffer by keeping him alive, and even if he did survive, it was highly improbable that he would walk, talk, or think like a typical child.

I lost two babies in eight months—doctors had no clue why. They did say this had to be genetic: two kids, same symptoms. The odds of having a third child with this were almost impossible.

As Mattie turned two, and with both him and Jamie needing full-time care, Jeni was especially exhausted and mentioned as much to her doctor, who noticed her drooping eyelids, a symptom of neuromuscular disease. She had a biopsy, which revealed not only that she had the adult form of dysautonomic mitochondrial myopathy but also that this rare condition, now named, would certainly kill Mattie, as it had her other children, and maybe eventually her.

Yet as Mattie continued to live, Jeni's dread turned into something else. She saw that he was an especially empathic child. By the time he was 14 months old, at a church picnic, with a trach in his throat, when other children were crying, he would walk around and kiss them each on the head. At three, he was reading billboards and writing, scribbling—he would recite to her how he felt about his dying brother, whom he called Mamie, and she saw him teach his stuffed animals the stories, and now her dread had been replaced by something like awe. When he was four, he heard about the Oklahoma City bombing on TV. Jeni told him, "Let's pray for the victims," and Mattie, though he was unable to articulate what the word meant to him, said, "No, let's pray for the person who did it; they don't have peace in their heart."

To be his mother was to watch him often from a distance, sitting in the thick of a crowd. To see people run up to him, squeal for him, hug him, need him. But before she was a celebrity mother, when she was just the person who knew him better than anyone, Jeni rented one-room apartments with leaky floors where he'd hold his pencils with bleeding fingertips and read 20 to 30 books a week. History, science, literature. He really didn't like algebra. "Why do I need it if I'll never grow up?" he asked. Sometimes she had the two of them living in basements, where he wrote at a small table for hours on end, at night under a blanket with a flashlight, his own little cave. They lived in a Marriott hotel for a while and with someone in a retirement village for a week, and spent the night in the hospital atrium even when he didn't need to be there, dreaming of what it might be like to have a fancy meal or two beds.

Jeni ended her marriage when Mattie was in first grade, and a judge granted her sole custody. She had insurance through the University of Maryland, where she was studying for her PhD in early-childhood special education, but she decided to postpone her degree to take care of him. She had two jobs—one at a nonprofit that was sold, leaving only her research assistantship at UMD, which paid a stipend of just $5,000 a year. She began to homeschool Mattie when he was nine because of his deteriorating health. This allowed him—a boy who'd readMoby-Dick several times and the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald—to begin auditing college courses, too.

In 2001, Mattie was admitted to the hospital and was so sick that he was asked what his three wishes were. He wanted to publish his poetry. Meet Jimmy Carter. And appear onOprah. "The problem," remembersOprahfield producer Shelly Heesacker, "is that a lot of people have a dying wish to meet Oprah." When Shelly went to Rockville to see if Mattie was a fit for an episode called "How Does That Feel?," she was going to ask him several different ways,How does it feel to have a neuromuscular disease?, wondering if he could even articulate the answer. They rolled tape . . . and he started talking about world peace. Eleven minutes and 43 seconds into the interview, she looked back at the camera for the time code, because she was so shocked at what she was hearing. He was 11 years old. "There was nothing normal about him. He looked like a kid, but he talked from a perspective that was beyond his years. At one point, I just said, 'Well, why is peace so important to you?' And he said, 'We're fighting over our differences, and our differences are our true beauty. We're a mosaic of gifts and I can't understand why we can't get along like me and my mommy do.' I thought: Does he even know what mosaic means?"

Shelly told her boss to tell Oprah:This is bigger than just one segment of one show. Jeni remembers the moment—when the credits started to roll on that first episode, October 19, 2001, 4:59 pm EST. Mattie had been a local celebrity in Washington, on the news in stories about a singular family with a rare disease, but during that episode, Oprah talked to Mattie for several segments more than scheduled. Afterward, he was onGood Morning America and onLarry King, wearing suspenders in homage to the host. To watch Mattie on TV was to comprehend the urgency of him, his tiny body wiggling in his giant wheelchair amid the tubes that kept him alive, the chair an omnipresent life-support system like a frame around him wherever he went. But there was something about him, something about the way he looked, the way he sounded—his small voice interrupted nearly every second by the oxygen from his trach—that connected with audiences. He seemed upbeat while talking about what he knew to be a terminal illness, a kid who had been dealt the worst hand, softly whittling a gigantic idea down so everyone could understand it. In a post-9/11 world where people were newly terrified, it was as if they wanted to hear him soothe them, to tell them peace was possible.

Mattie and Jeni were befriended by all kinds of politicians and celebrities—Laura Bush, Jimmy Carter, Bono—enamored with Mattie's post-9/11 message of peace. Photographs of Laura Bush and Bono by Getty Images. Other photographs courtesy of Jeni Stepanek.

Oprah and Mattie began to call each other, e-mail each other every week. She helped him find a publisher who would mass-produce his books, and she bought Jeni the Econoline to go meet his readers across the country. They'd drive while singing the Pizza Hut song and arrive at a book signing, where thousands of people waited to see the boy who slept with Mr. Bunny. The same boy who could be a surly 13-year-old, shouting and slamming the door in his mother's face. Who wanted to hang out with his friend Chris Dobbins and an older crowd of teenagers, guys who smoked cigarettes, who had tattoos, who watched R-rated movies and talked about girls.

I wish I could've said his fame made me feel really good, but I can't. It was both wonderful and overwhelming at the same time.

For Jeni, there was a mix of pride and trepidation, thinking about how her son no longer completely belonged to her. Watching Maya Angelou, the poet Mattie most revered, have him sit with her at a book signing. Hearing her tell him, "Some of your poetry is profound, some of it is simply pleasant." Being at the Mall of America in front of a crowd that filled every level, and with Jerry Lewis at the Muscular Dystrophy Association Telethon. Being at an event where a mother came up to his wheelchair and grabbed the handles and, manically, refused to let go until security had to intervene. Looking above his bed in their apartment in the later years and seeing the poster of Liv Tyler he had kissed so much that he rubbed her lips away. Knowing he was also in love with Emma Watson, whom he would eventually meet. Remembering that Amazon reviewers castigated him, complaining that the whole thing was made up and the only reason any of it had ever happened was because he was sick.

This was happening while Jeni herself was diminishing. It was happening while Mattie was in the hospital coughing up blood, while the trach had denuded his airway, the skin sloughing off, and while he was having bouts of respiratory distress. She'd meet with doctors to go over every possible treatment they could think of—would the side effects kill him?—and ask Mattie his opinion on how to proceed.

"I wish I could've said it made me feel really good, but I can't," Jeni says of her son's fame. "It was both wonderful and overwhelming at the same time. And I still feel that. I have to tell you, it honestly wasn't until years after he died that I began to get a sense of who my son really was in this world."

Jeni learned that studying people was one of Mattie's gifts, to say nothing of his way with words. One of his favorite things was to ride his wheelchair to the coffee shop or the ice-cream parlor. He would go to the local Safeway and introduce himself when people walked through the sliding doors—he knew the manager there, and the butcher. She knew him not as some wunderkind, some magical boy, but as a kid who sprayed whipped cream into his mouth every year on the last day of school, who cried when he held his best friend's daughter, knowing he would never have a daughter of his own. She remembered how much she loved to hear him talk, to sit and have tea with him at the little table in their condo in the afternoon.

But there was one thing she didn't want to think about, or even entertain. From 2003 to 2004, after he turned 13, he wanted to talk to her about this feeling that he was going to die, and about her plans after he was gone. She wouldn't listen. He told her best friend, Sandy Newcomb, "You've got to tell my mother I'm dying."

"He was saying,I don't see summer camp, I don't see Thanksgiving. This is going to happen, I don't know when, but it's happening. And you need to accept this. It was during those months that I really did not do what I should've done for my son," Jeni says. "I was there for him. But I could not be there with him. I'll regret that till my dying breath. Saying to him, 'I'm sorry, I'm scheduled to have coffee with Sandy,' or 'Hold that thought, buddy.' I did everything I could to end the conversation quickly. Even in his final weeks, I encouraged him to be strong. I should've just sat there and held him."

Mattie went to the hospital in March 2004 and had three separate cardiac arrests—the first stopped his heart for 45 minutes. He was revived each time, and his eyes opened up, but in them was a heartbreaking sheen of recognition. Eventually, his muscles contracted so tightly that he lost the ability to speak. Even his bones began to break. He never went home.

"I would go in and give him a bath while Jeni was resting," Sandy says. "He got dystonia. His hands got so tight that the circulation cut off, his fingernails came off. By the end, his tongue was so tight in his mouth—it came from damage in the basal ganglia, part of the disease progression. I said, 'Wow, look at that, your arm moved more than it usually does!' And he just looked at me, and this tear rolled down. I said, 'I know—it's not moving as much as you would like it to.' "

It was breaking news when he died, across the world. Sean Astin, Mattie's favorite actor, showed up in Washington in a taxi after he heard and said, "I didn't know what else to do." He and a small group of family and friends and some firefighters Mattie had befriended after 9/11 attended the private viewing at the funeral home. Jeni was comforted that Sean just sat with the family, and they stayed up late that night in her condo, the night before the funeral, when thousands came. Afterward, Jeni buried Mattie with, among other toys, Mr. Bunny and his fart machine.

In the months after, when she was no longer at the hospital talking to nurses and doctors who had become friends, no longer caring for Mattie, Jeni lost the will to live—she decided to lie in bed until she died. She figured it would take 13 days. This hit her around 13 months after he was gone, in the summer of 2005. "I thought, 'I can't go back to normal,' " she says. "Normal, for me, was parenting him."

I was there for him. But I could not be there with him. I'll regret that till my dying breath.

Her friend Sandy, who at the time lived in the condo next door, said, "You haven't come for coffee. Are you coming over?"

"No, I'm done."

Sandy sat on the bedroom floor and refused to leave. Sandy, who had met Jeni a year before Mattie was born and helped raise him, said, "I understand that this is hard, I respect that, I'm not going to let you go through this alone. . . . You can't just stay here and die. What if you get hungry?" She volunteered to sit with Jeni.

Jeni said, "Fine, suit yourself, stay here." She harrumphed and rolled over in bed. Eventually, when Sandy wouldn't leave, Jeni rolled out of bed and into her chair.

"You've changed your mind, then?"

"No," Jeni said. "I'm getting up to roll over you."

For a while, Jeni kept a journal about her life without Mattie. She realized what he'd told her when he said "forthward"—he had commissioned her to take what he left but to use it how she wanted. She didn't speak like him, didn't write like him, and now there were all these empty places where he used to be. But she reshaped his message in her own voice, and that was a power that opened up her life. "I take what he left behind," she says. "Some of it exactly as it is; some of it I've repackaged so it fits better with how I speak, how I teach."

She was in a wheelchair; she always would be. She was using oxygen; she'd always need to. Her muscles were weakening, but she otherwise began to flourish.

She turned his message into a small industry. In the years after he died, she took the trading cards he'd made and had more printed to distribute them, each with a quote from him or a line from a poem. Cards for resilience, service, education, a card for choices to balance blessings and burdens. Kids could pass them around and never forget him. She helped raise money in his name to send 30 teenagers from around the world to New York to teach them about Mattie and his core belief:We are a mosaic of gifts. It was the Just Peace Summit, and Jeni sat onstage and told the students her own story, teaching them how to write an elevator pitch, a proposal, a grant. She got the nickname Mama Peace.

"When I think of Jeni, I never think of her as someone who's sick," says Lulu Cerone, who attended the summit in 2012. "That's not what comes to mind. I think of her as someone who's strong and wise. She's optimistic without it being contrived. She always has hope, even in the most dire situations."

The town of Rockville took a plot of land and established a park dedicated to Mattie. Jeni worked with a graphic artist who read his books to design the layout. She became head of the Mattie JT Stepanek Foundation, an endeavor to promulgate, as he said, that "peace is possible."

Jeni had promised Mattie she would get her PhD, and she did, in 2008, with honors. She began to teach at the University of Maryland, and was traveling, and appearing on Oprah's 20th-anniversary special to talk about Mattie's life. She looked well and happy.

Then two years ago, she got cancer.

"I've outlived all my prognoses," Jeni Stepanek says.

It's May 2017, a bright day in Rockville, and she is wearing a funny T-shirt with a T-rex cartoon, her graying hair cut short, and she has small round glasses and dangling earrings in the shape of peace signs. Barely visible beneath the shirtsleeve on her right arm is a medicine port that goes into her heart. She is drinking a glass of red wine. Sitting in her chair on the hardwood floor of a kitchen in a big house she shares with Sandy and Sandy's family, she is describing herself asdecrepitand chuckling with a shrug of her shoulders. "I have so many conditions that when you treat one, it exacerbates another one. And then if you treat that, you trigger this over here. I'm constantly slapping Band-Aids on my body systems."

In 2015, she went to the hospital, hemorrhaging out of the blue. She was diagnosed with cancer and had surgery to remove it; she then began weekly chemo with daily radiation. But the chemo treatments damaged her kidneys, and the radiation caused fibrosis of her intestines due to her underlying disease. Effectively beginning the end of her life.

She can feel it now, and see it. All over her body. Swollen feet with severe pitting edema—she keeps them, unmoving, in a Redskins cozy on the chair. Her feet feel as if they're going to pop. Her heart beats too fast, and sometimes too slow. She needs open-heart surgery as well as surgery to correct her scarring intestines, which could burst at any time; they cause her to vomit a few times a week, but surgery is much too risky to repair any part of her. She has a soft, almost scratchy voice. Every few seconds, she turns her head slightly to her right and places her lips on a tube connected to a tank of oxygen, which kicks an automatic gust of air into her lungs.

"It's always something," she says, in the same manner that Mattie explained his disease to Larry King. "How is it that I'm sitting here today, in 2017, divorced, disabled, juggling multiple life-threatening disabilities? I would say I have, relatively speaking, some shreds of sanity. And . . . I am happy. I am a woman who is filled with gratitude. I am rooted in a motto. Celebrate life, some way."

In the Rockville house across from Mattie's park that Jeni now shares with Sandy's family, they celebrate life. Two kids are running around, Sandy and her son and his wife are yelling jokes, and the big bulldog, Bentley, is romping about. Though Jeni struggled to make a resolution in 2017, for the first time in her life—though she can feel something coming, like a premonition—she does not seem burdened by it.

Jeni is an obsessively organized person, a trait she makes fun of—a coping mechanism. To pass the time as a kid, she liked to draw. She would sketch houses, city blocks, yards, fences, a community. She would name each of the families. "I would go crazy if they weren't in the right order," she says. "I needed to be putting order into the world. The planning of order, which mattered more than playing it out. Planning a fictional party—not having it."

Her CDs are in alphabetical order, her socks arranged by color, sometimes by fabric, and food in the cabinet by nutritional group. That tendency is something she gave to Mattie, who had to flip a light switch three times before leaving a room.

"After Mattie died, I started thinking: What ismy heartsong? I thought it was to be a mother. But his message is that you give your heartsong away. I realized all my life, I struggled with knowing that I mattered. Knowing that I had purpose. As a child, I felt like I mattered only if Ipleased someone. Thatmattering was contingent on things that I did. As a parent, I began to realize that's what I had been giving my children across those 20 years—I was giving them the gift of knowing you matter. And to love for the sheer sake of loving and expecting nothing in return."

Every morning, she pushes herself off the bed and into the bedroom where she organized some of his things, a room thick with his memory, his presence. His Mead composition notebooks full of drawings and ruminations, his journals. A collage of photos that keep him in view, on a board directly facing the bed, the boy in the round glasses and floppy fishing hat all those years ago, in his wheelchair with his friends, wearing his red robe and black belt in karate, an oxygen tank beside him. The letters she still receives from prisoners at Rikers Island, who had discoveredHeartsongs.

"I think about the end of my life and I say . . . okay," she says. "Which to me is a combination of Mattie's message. He says: Peace begins with being able to sayI'm okay. And that can only happen if your basic needs are met. Then once you're okay, peace is when you can look at your neighbors and say: Are you okay?

"I've never witnessed more physical suffering than what he went through. He would be in pain, but he would think of other people, and he challenged me—he told me, 'Choose to inhale.' I draw strength from that."

He would have been 27 in July, gone nearly as long as he'd been alive. And if she were to be gone next year, then she was determined to keep Peace Day going. The day is an annual celebration of Mattie's teachings timed to his birthday, usually a day with balloons and cake and fireworks. Normally she would have organized it herself, across the street in his own park, but she couldn't now—she was too weak, so the mayor of Rockville was sitting in her living room in May helping her plan, Jeni scrolling through her iPhone.

"We're going to start hanging advertisements around the city," Jeni said. They showed the face of Mattie's statue, wearing a birthday hat beneath the slogan "Make Peace the News!"

Jeni met with the owner of the King Farm neighborhood restaurant Botanero, where the party would start—Sandy's son Chris would be the guest bartender, making Sunset Cervezas, in homage to Mattie's favorite time of day. Then the party would spill into the little park next door, with tents, the city closing the streets. Jeni pictured a deejay, and revelers going around to different peace activities, learning about Mattie. A local band would perform. Her dream, her mission, was to get a day on the national calendar that celebrated Mattie's message of peace. That's how Mattie always thought—in big terms. Rockville's mayor had agreed to write the day into permanent commemoration in the town. It was a first step.

Jeni could see Mattie's park through the windows of the house. It was wide and green and glistening in the summer, children climbing on the swing set. After the meeting, she put on a green visor and sunglasses and took her wheelchair around to the back of the house, down the ramp in the garage, and down the sidewalk.

The wheelchair made a constant whir as she went up the concrete pathway, casting a last, square shadow, past benches carved with sentences Mattie had written—"Remember to play after every storm!"—then to the kiosk that marked the peace garden: "Peace is possible . . . it can begin simply, over a game of chess and a cup of tea." Pressing each of the four buttons on the kiosk makes Mattie's voice crackle to life and say something different. She paused there for a minute, then looked at the statue of her son in the middle of the circle. The short hair, in bronze. The trach wrapping up to his neck, in bronze. The bronze gap between his two front teeth, the bronze khakis, the bronze book in his lap. His bronze dog, Micah. Sometimes when she went out to see him, she found flowers at his feet or plastic glasses on his nose.

Tonight, a group of teenagers came, giggling, breaking the silence. They were looking around at the chess tables surrounding the statue, the football field beyond, the tables made of stone, where they sat down. Jeni was just away from him, the wheelchair and its equipment framing her, on top of the personalized bricks—WE CHOOSE PEACE,the Dimick Family; Miss U Mattie, LOVERon and Helen. Two families were walking the sidewalk. The group gathered around the kiosk near Mattie's statue. Jeni watched them silently, the visor protecting her face from the dwindling sun.

Mattie's favorite color was the sunset—orange, purple, with a tinge of bright pink. Jeni often sat with him on a pier in the Outer Banks, where they vacationed with Sandy's family, watching him watch that particular color. It was the place where he described to her both how close he felt to death and how much closer to something greater, his presence fading, his purpose growing, as the color—colors—he saw faded and darkened beyond the line of the ocean. He had written during his last year,I just like being able to see / The sunrise, and sunset, every day / in one piece, and have the breath / To say, "thank You" for such gifts / Here, I will stop leaving memories / For this Time Capsule, / So ten, fifteen, / However many years later, / You may remember these things / That mattered to a teen named Mattie.

One of her favorite pictures was taken when she'd stumbled on him once, alone, standing there, back when he had the strength to stand—looking at the water and sky, his small head silhouetted in a line of the fading sun. She had wondered what he was feeling, what he was thinking. And when she was in the park, his park, with the families looking at the statue of her son, in the sunset, beneath his color, silently considering him as if he were on their pier, the lambent light fading from orange to purple, both living and dying at the same time, she knew.

Justin Heckert (@justinheckert on Twitter) has written for GQ, ESPN the Magazine, and Garden & Gun.

Source: https://www.washingtonian.com/2017/07/30/jeni-stepaneks-last-heartsong/

0 Response to "Thaddeus Rex Running in the Sun Again"

Post a Comment